LUXEMBOURG IN TRANSITION

Reimagine territory: soil & people

Regenerative planning to face the climate crisis and overcome the status quo

cliché and consternation

Luxembourg is a fairly unknown and unpracticed territory; its cliché of rich country and the dominance of finance industry bonanza mask a nation which albeit having doubled its population within 60 years[1], massively mobilizes a greater region on a daily basis in order to manage its economic growth burden, blowing up the tiny 640.000 inhabitant population, of which 47% are foreigners[2], with 200.000 cross-border commuters[3].

Ultimately, this phenomenon evokes three conditions:

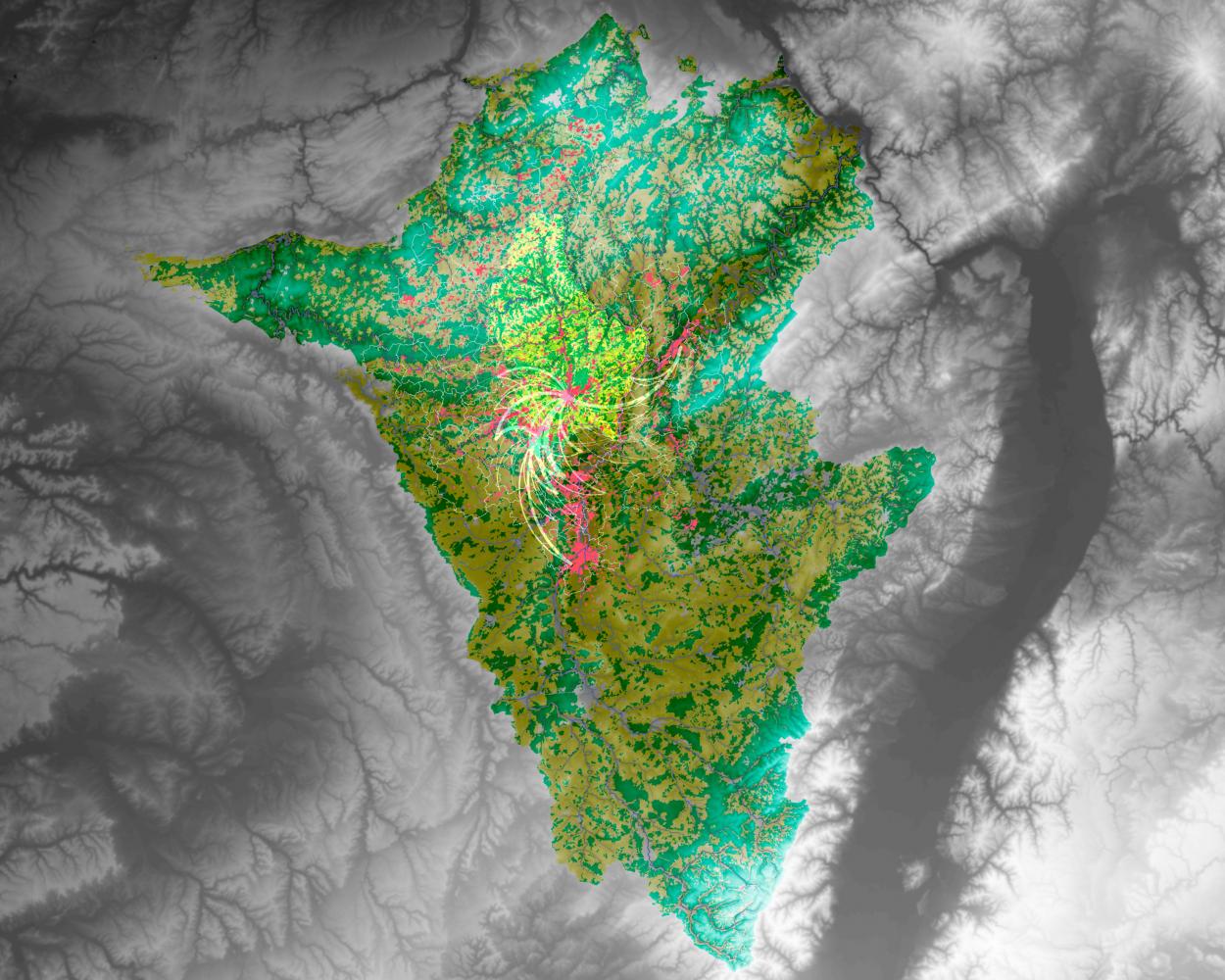

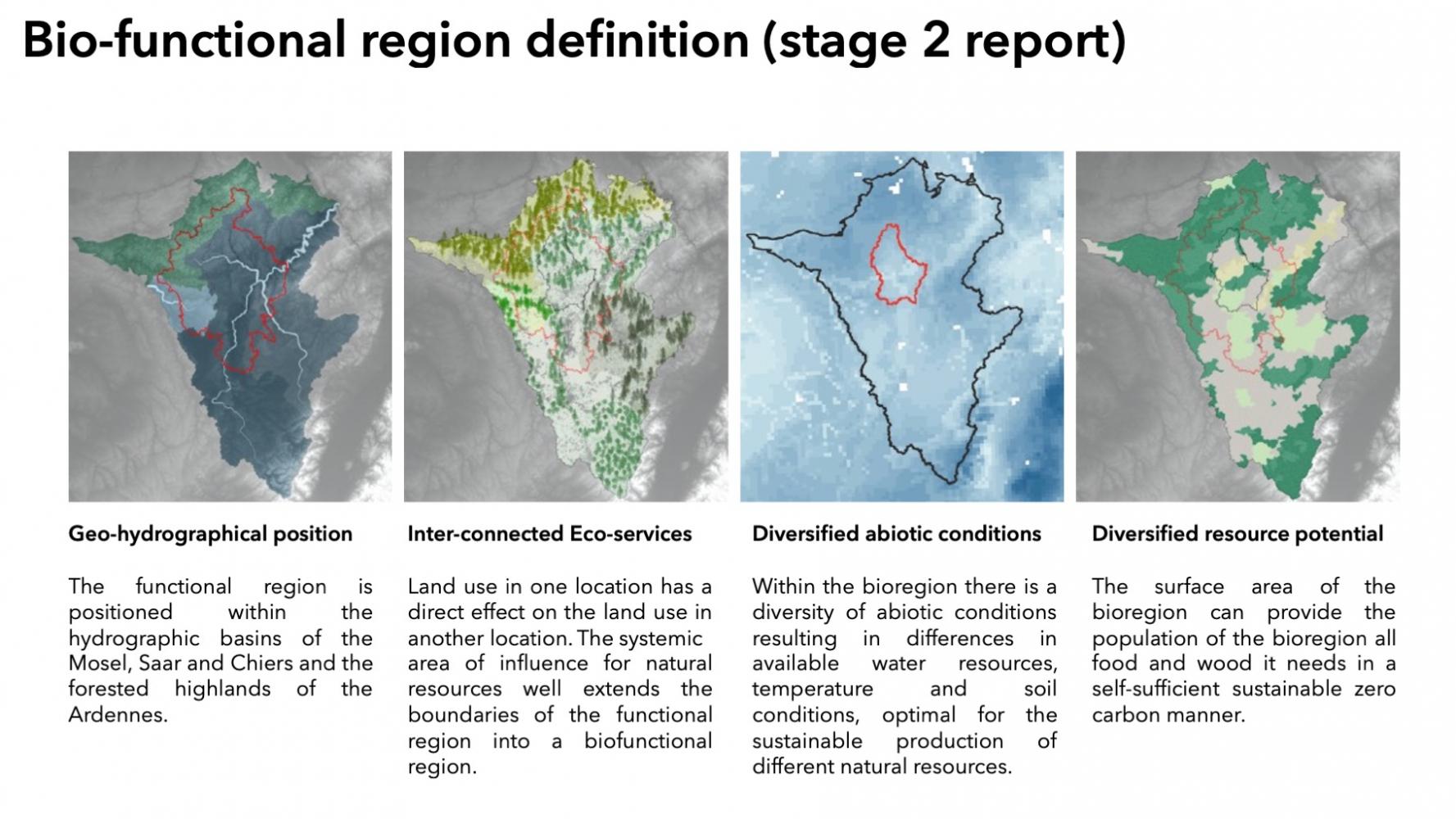

1. It draws a new territory: a functional cross-border region beyond the national borders, without which the country would be defunct.

2. A profound housing and development crisis

3. Deep socio-economic inequalities

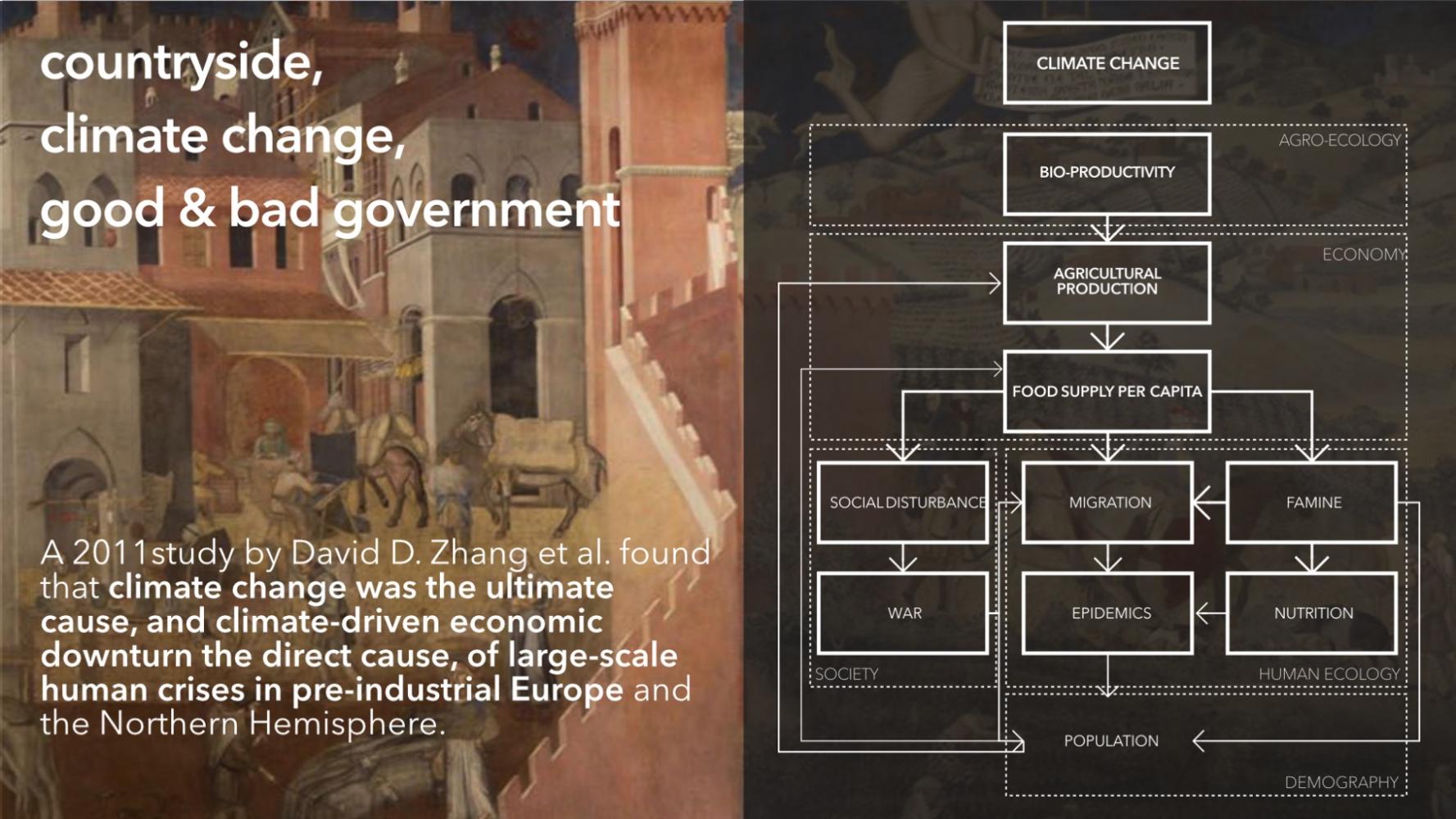

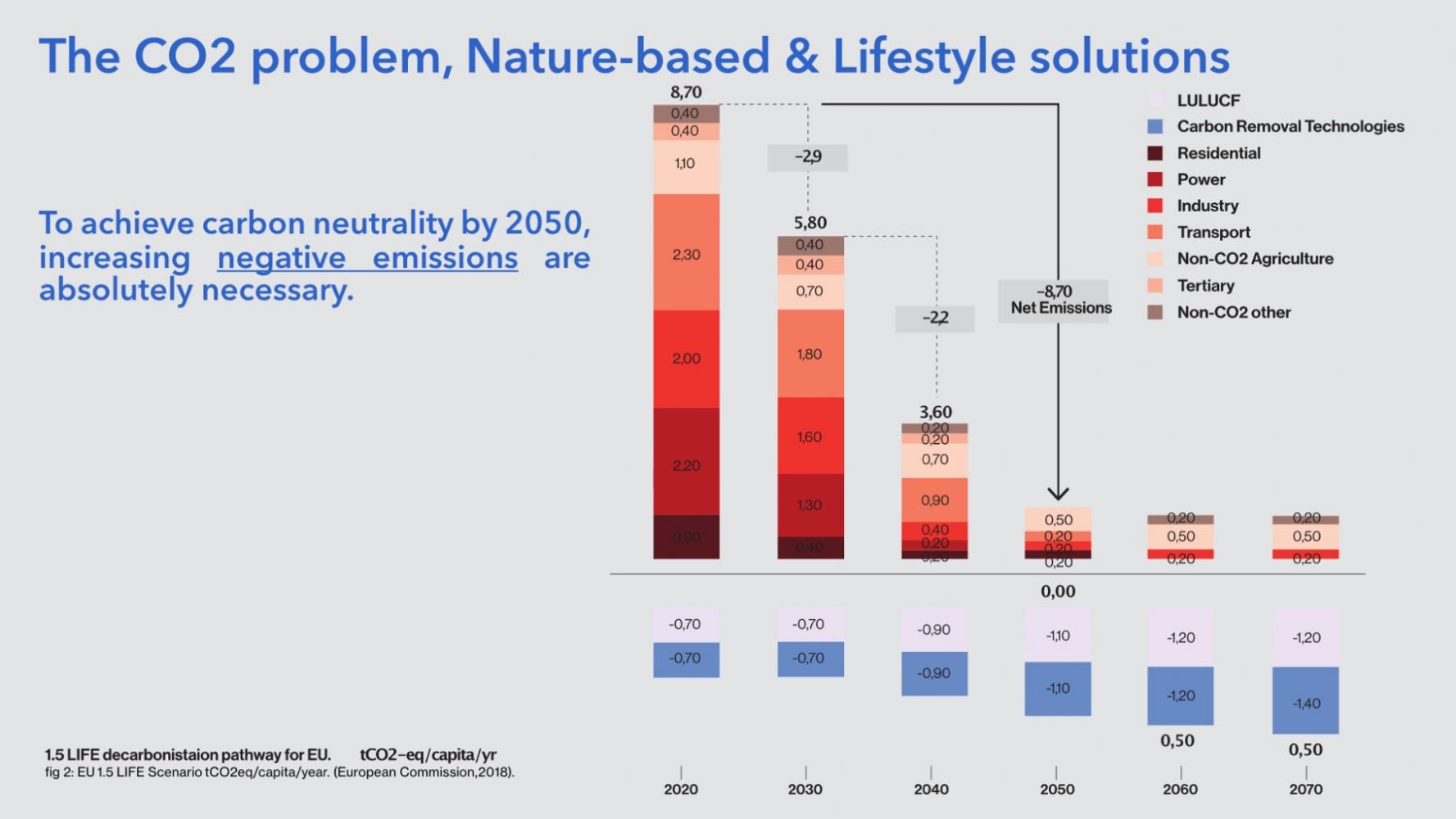

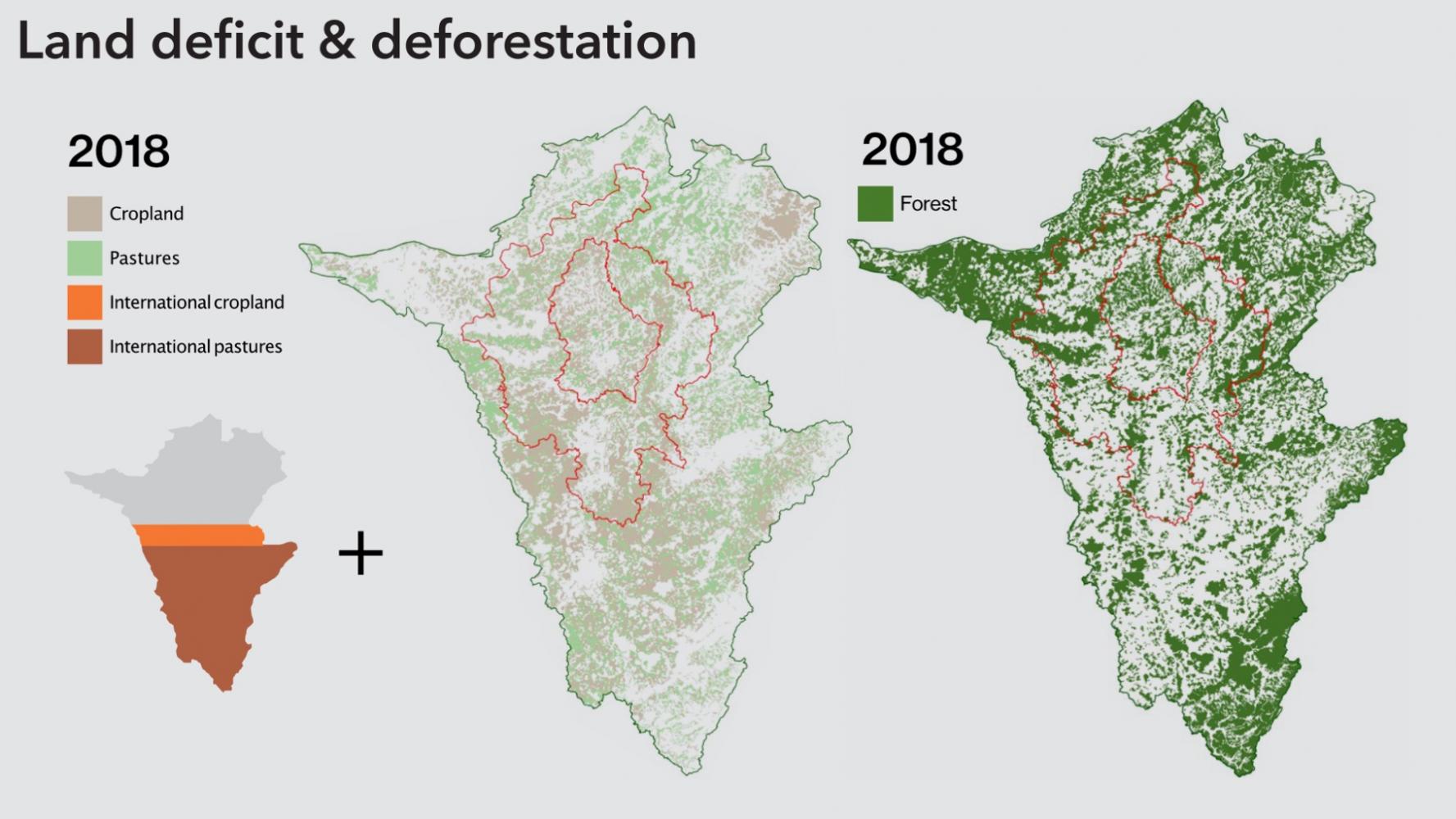

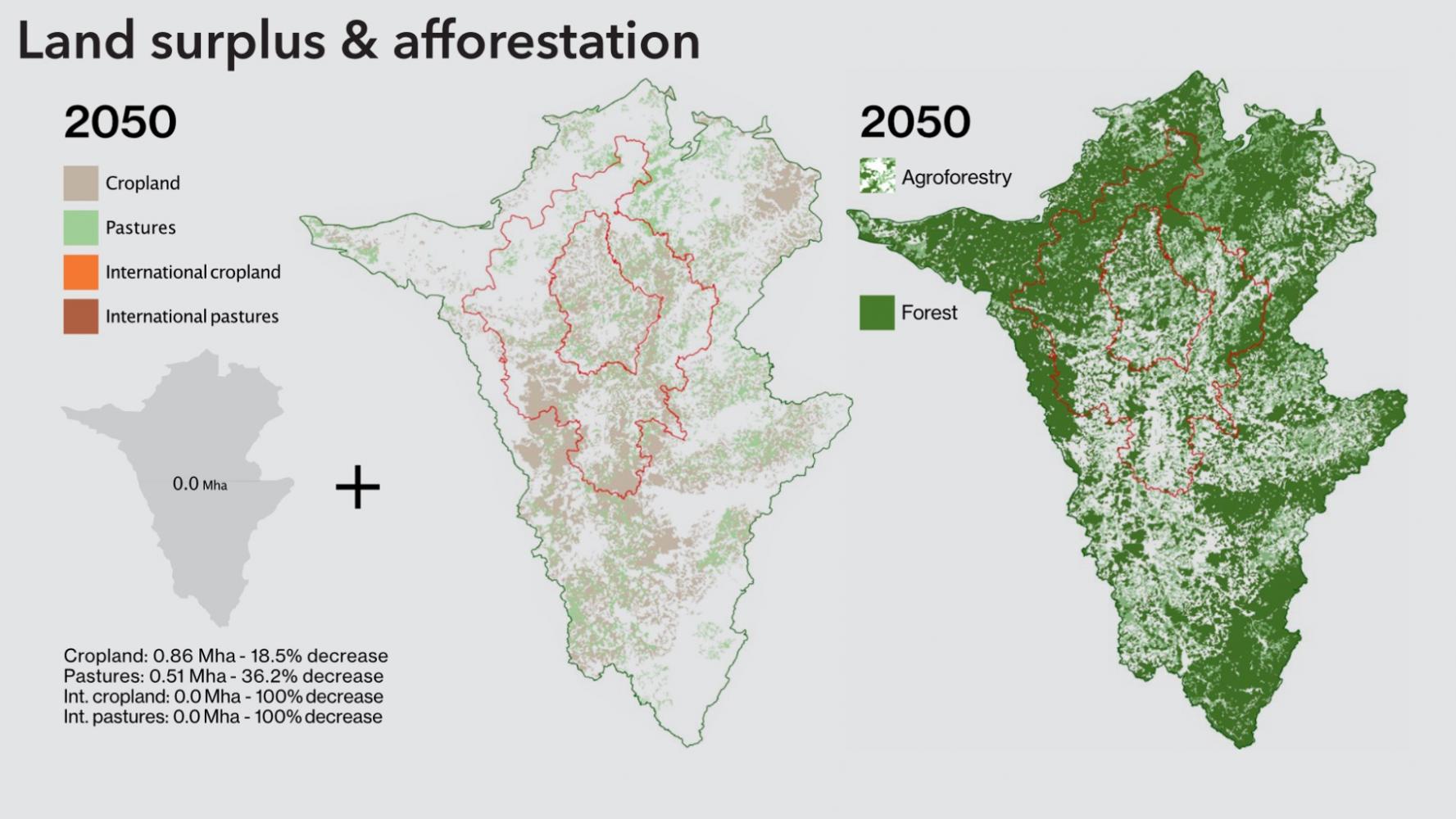

With the climate crisis, the territory is heating proportionately fast, exerting existential pressures on an already scarce water resource and the region’s characteristic forests.

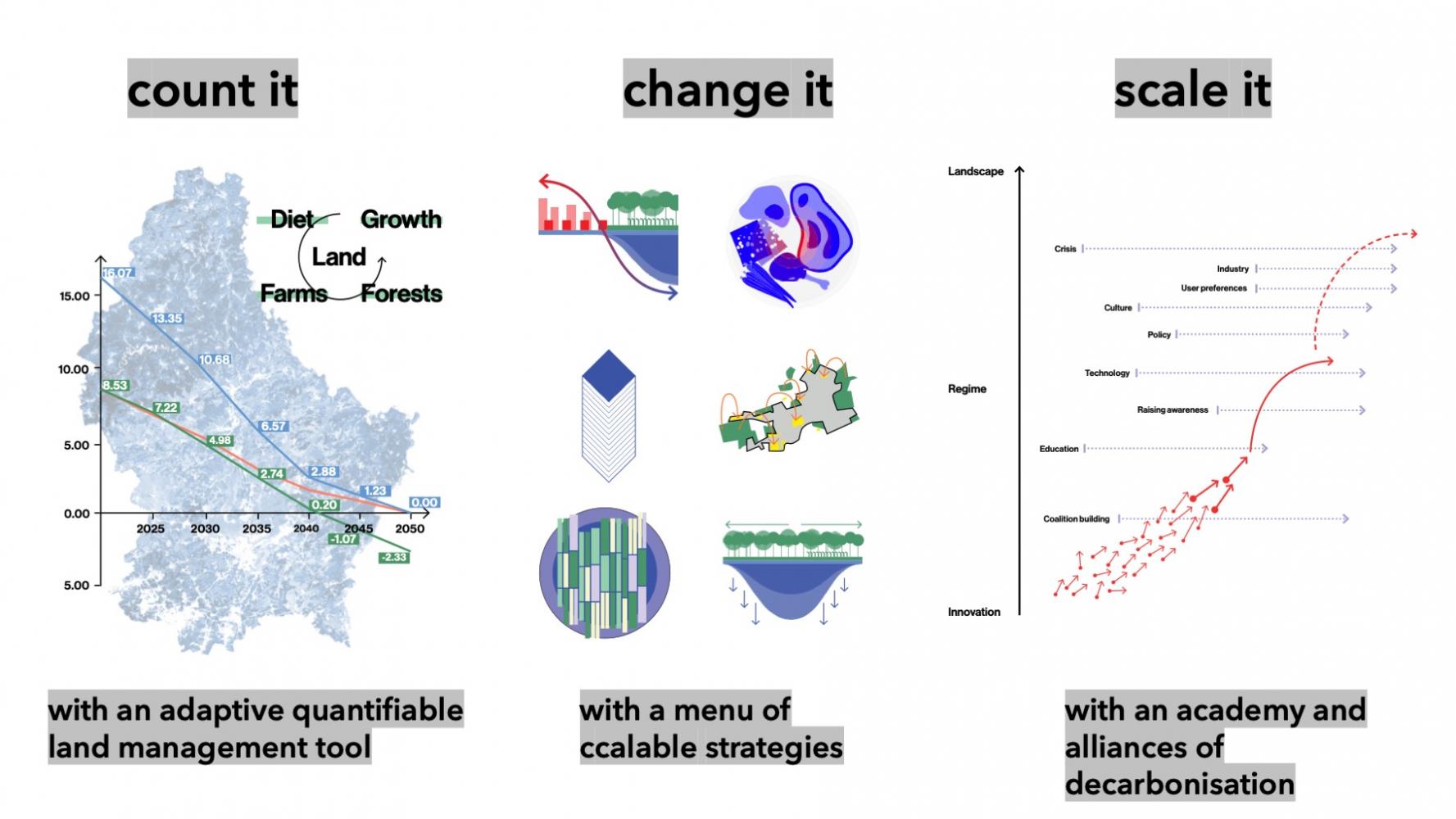

Launched by the Ministry of Spatial Planning, an international consultation labeled “Luxembourg in Transition” sought out to simulate the spatial implications of decarbonization according to the Paris agreement, and beyond, a quest to foster plans for a regenerative and/or resilient future.

Soil & people

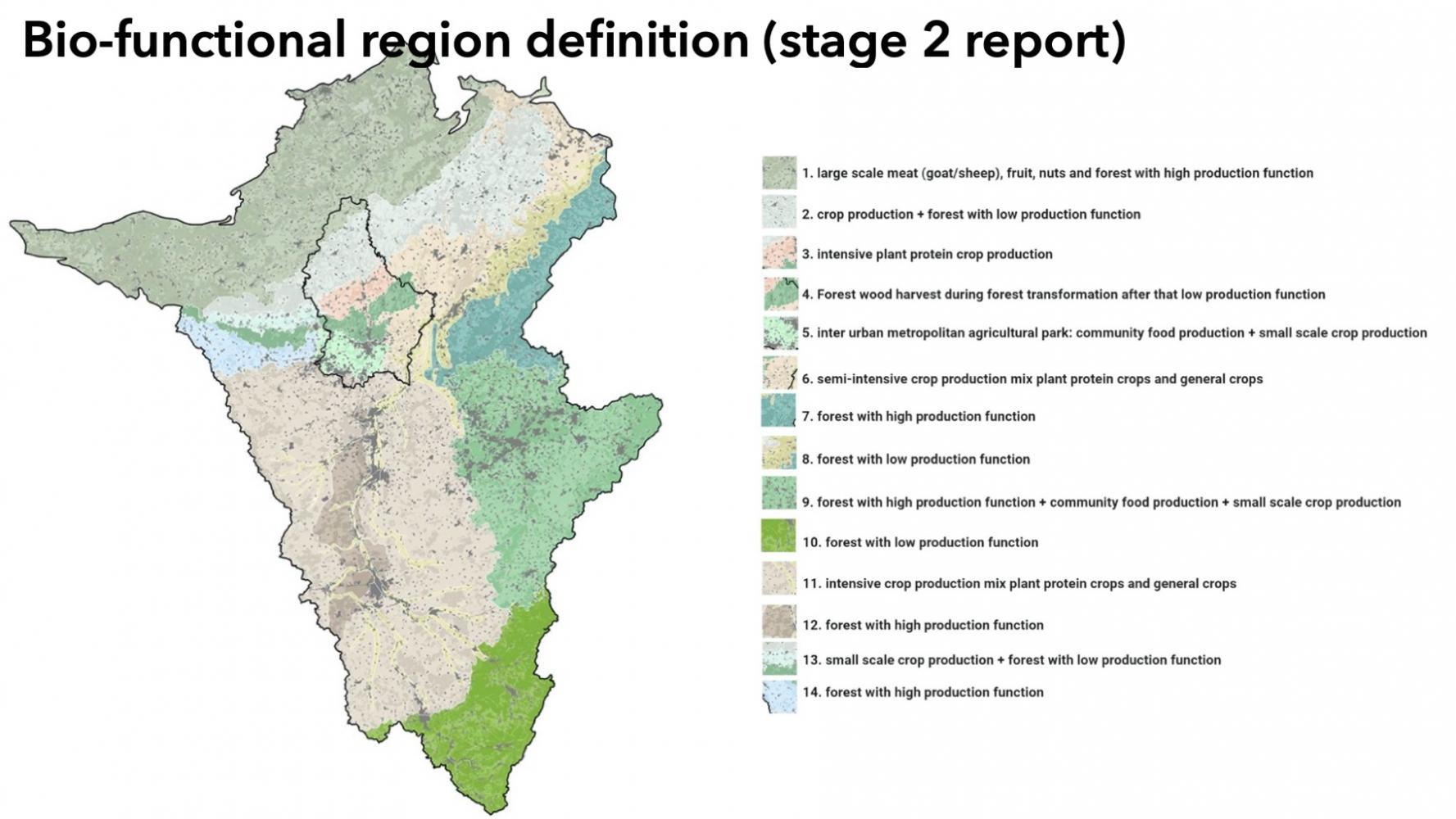

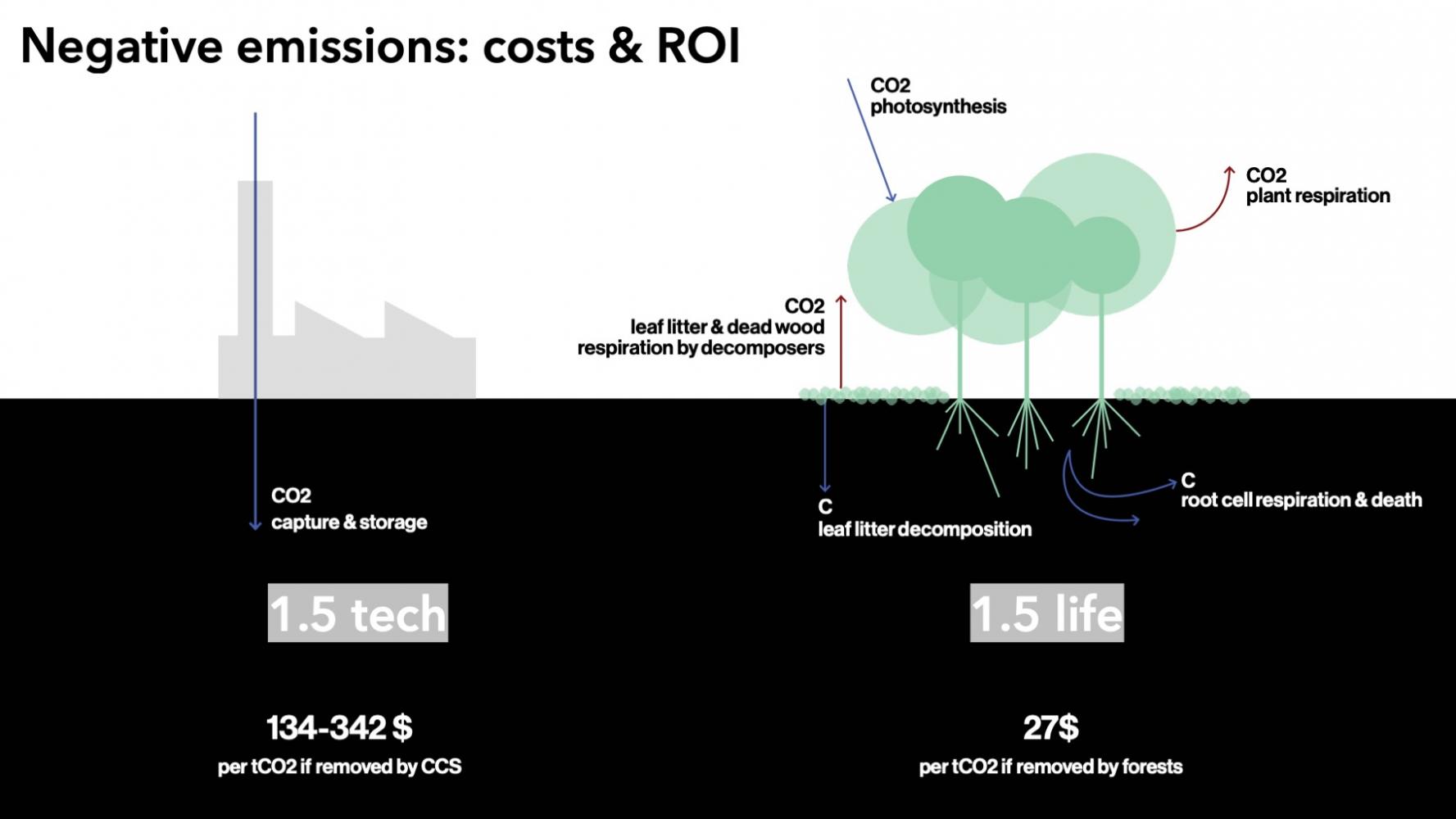

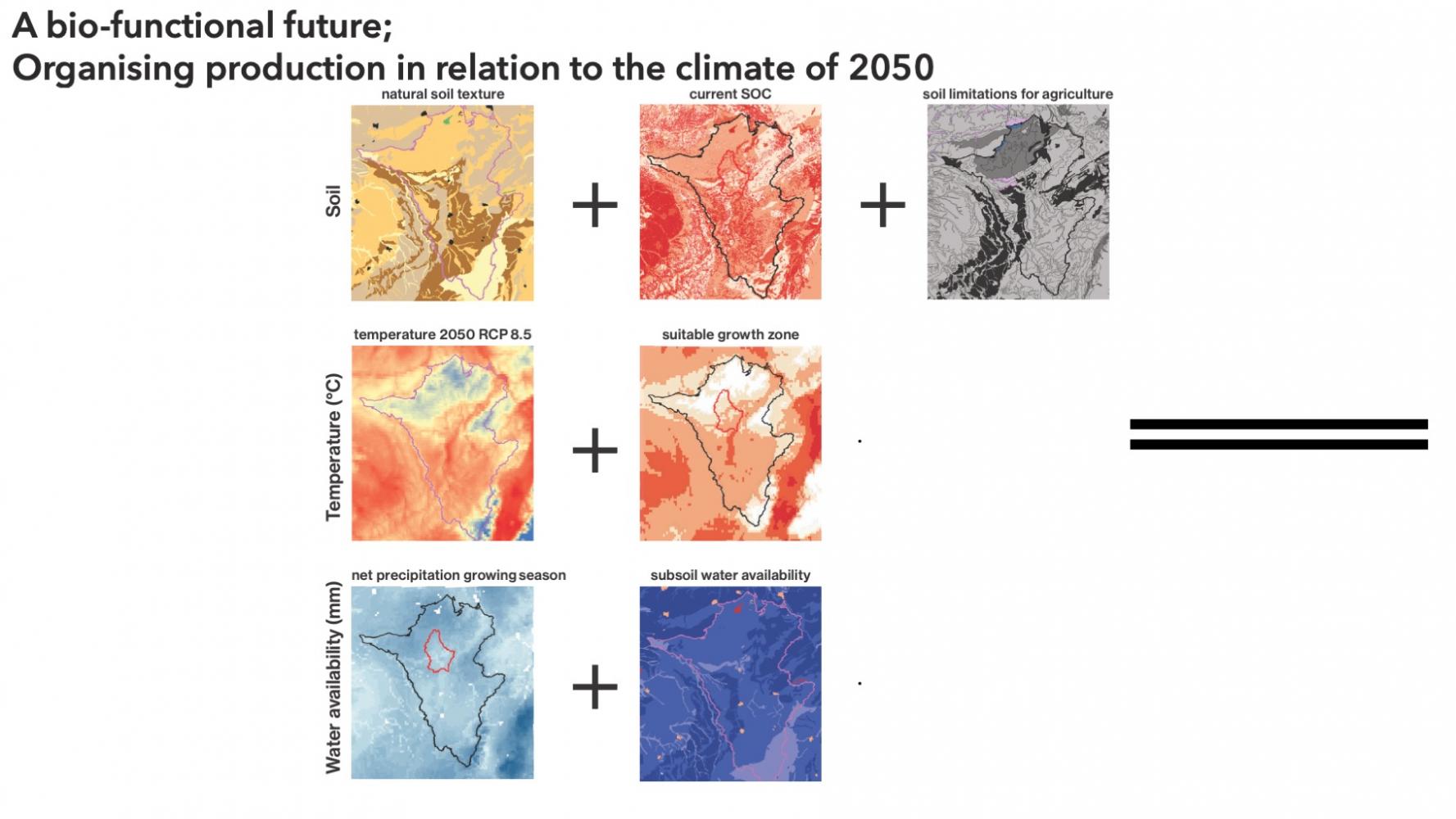

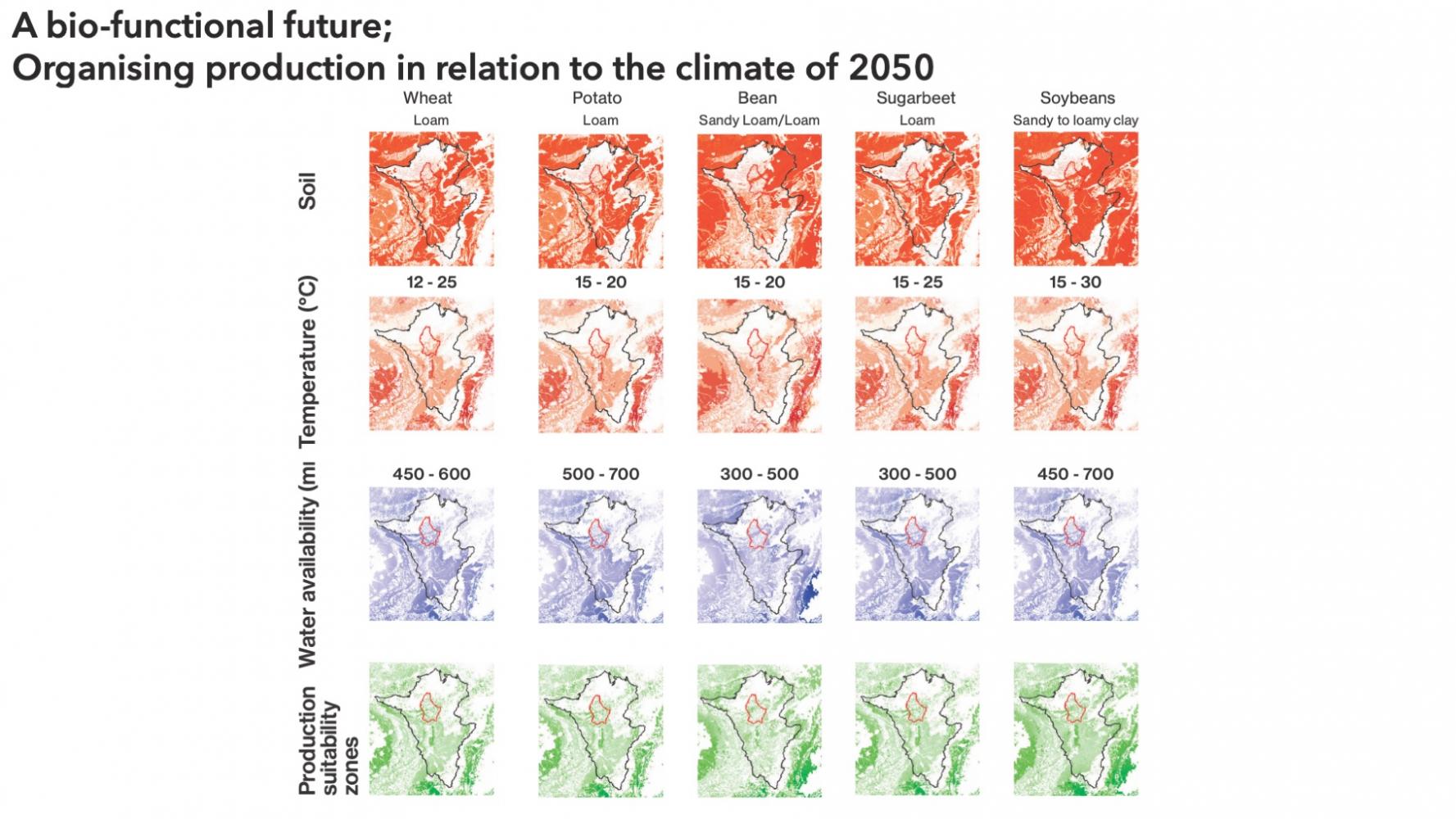

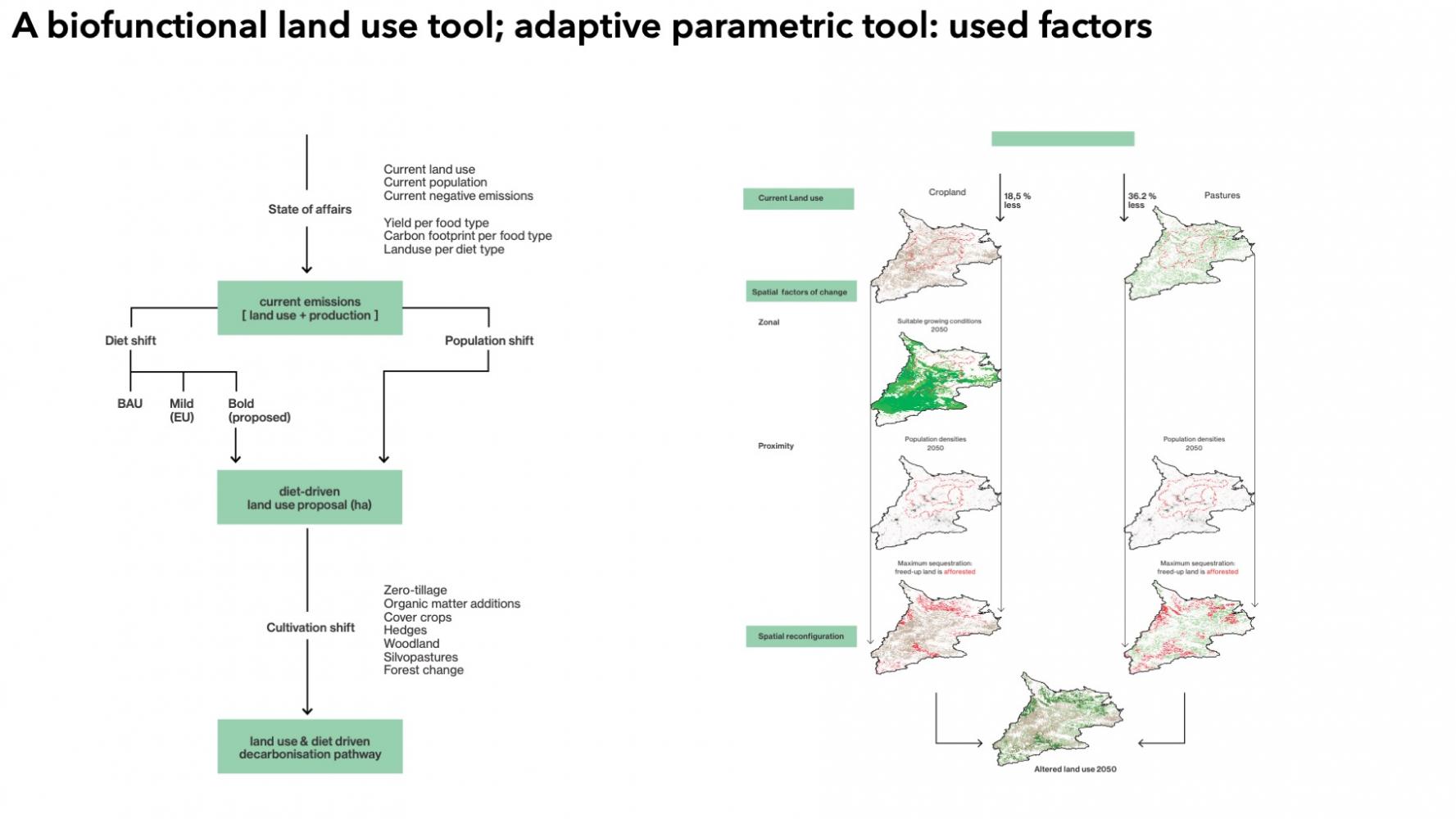

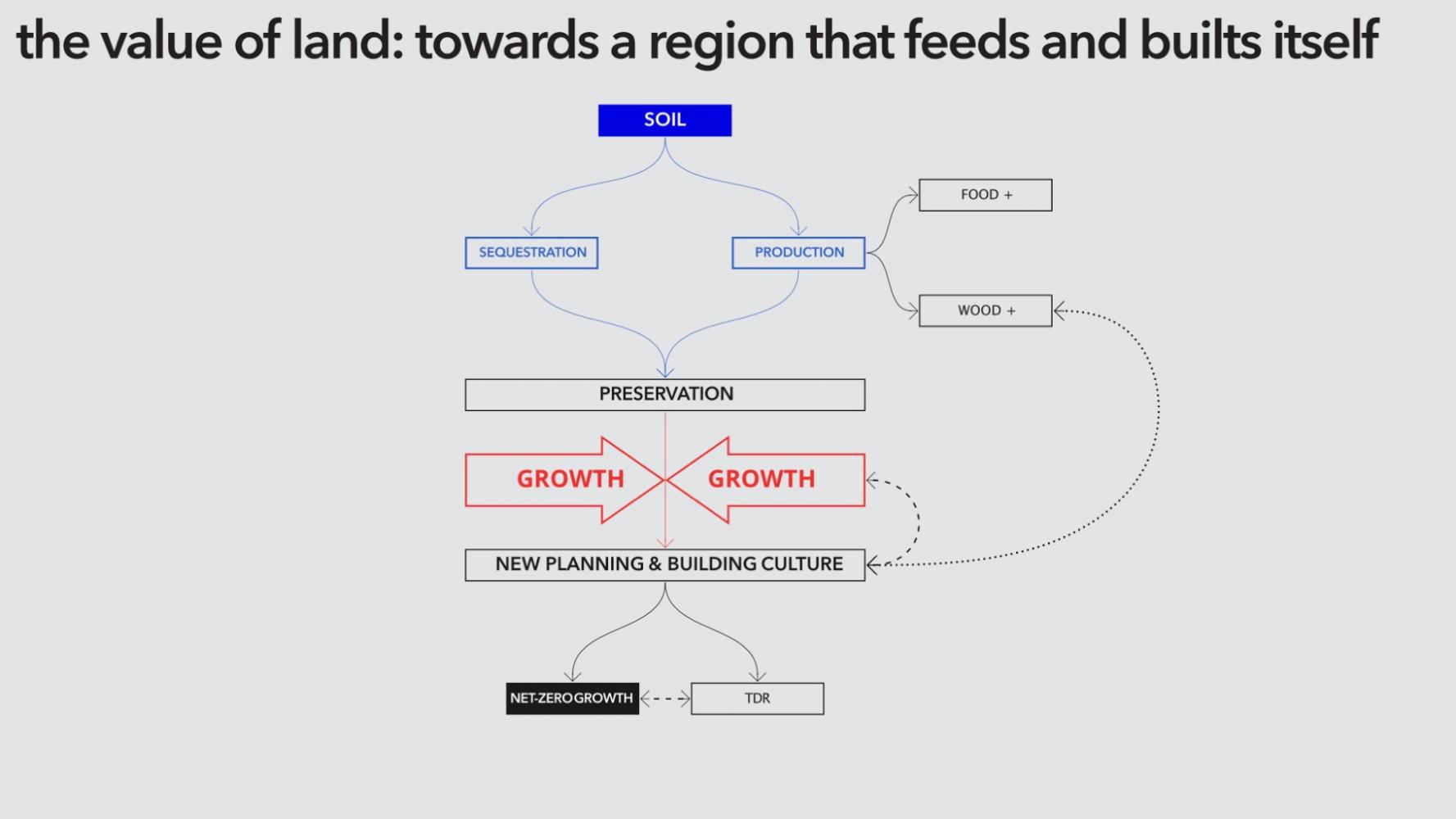

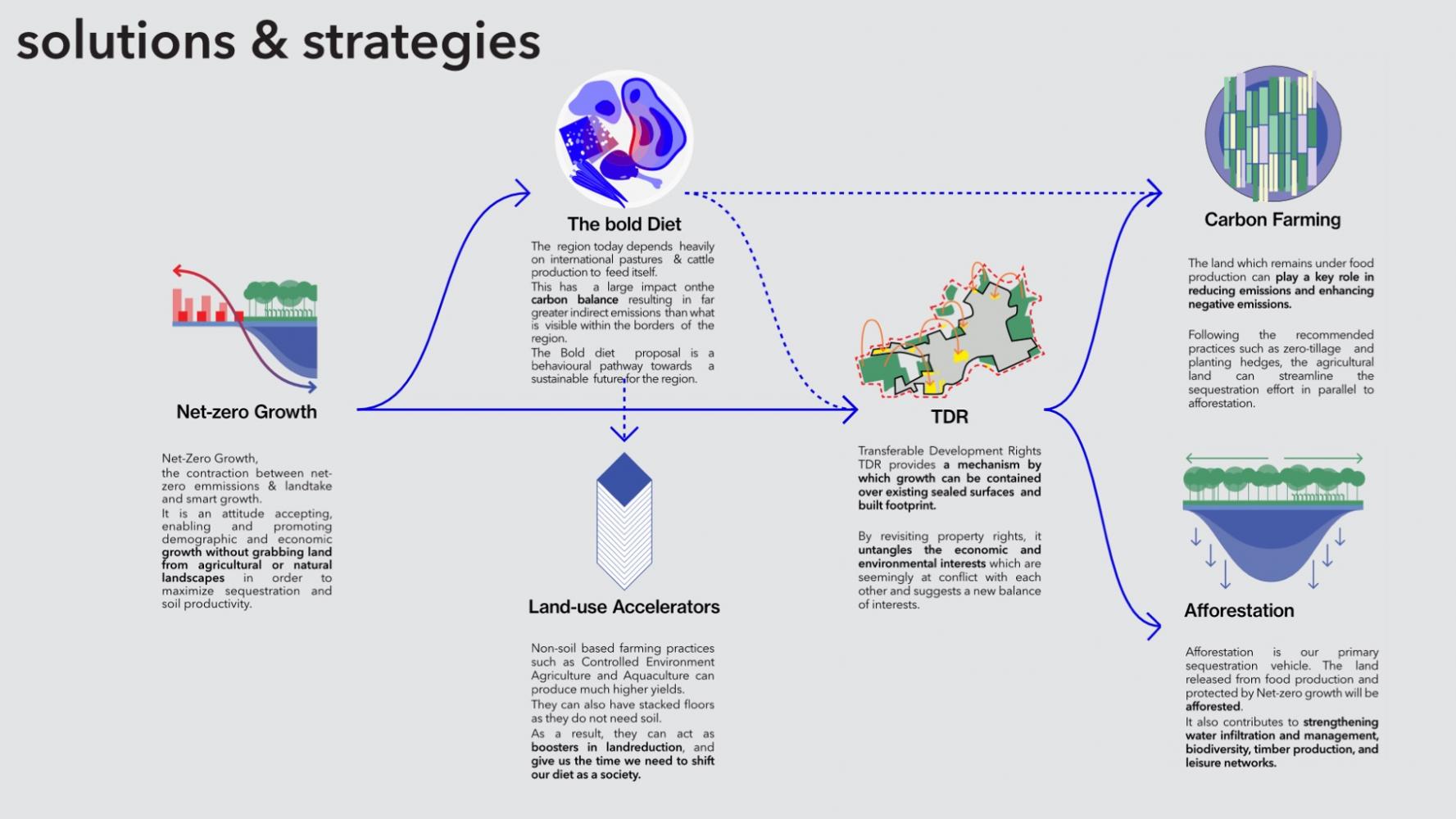

Focusing on nature-based and lifestyle solutions, the team 2001(lu)-51N4E(be)-LOLA(nl) sought to draft a new planning and building culture, mobilizing the regenerative and productive capacity of the territory and its landscapes, while sketching alternatives to land use and urban development.

All you can eat territory

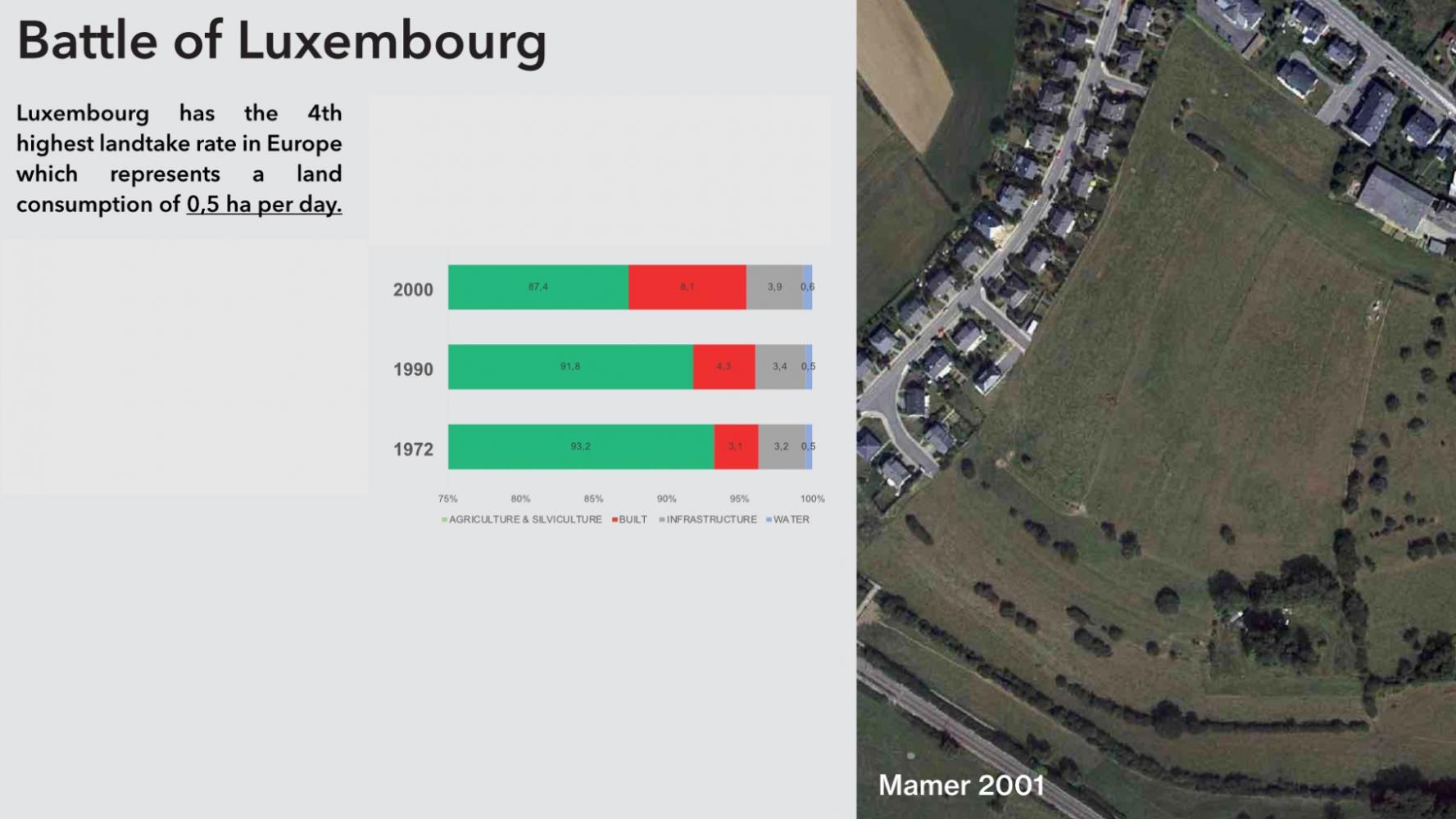

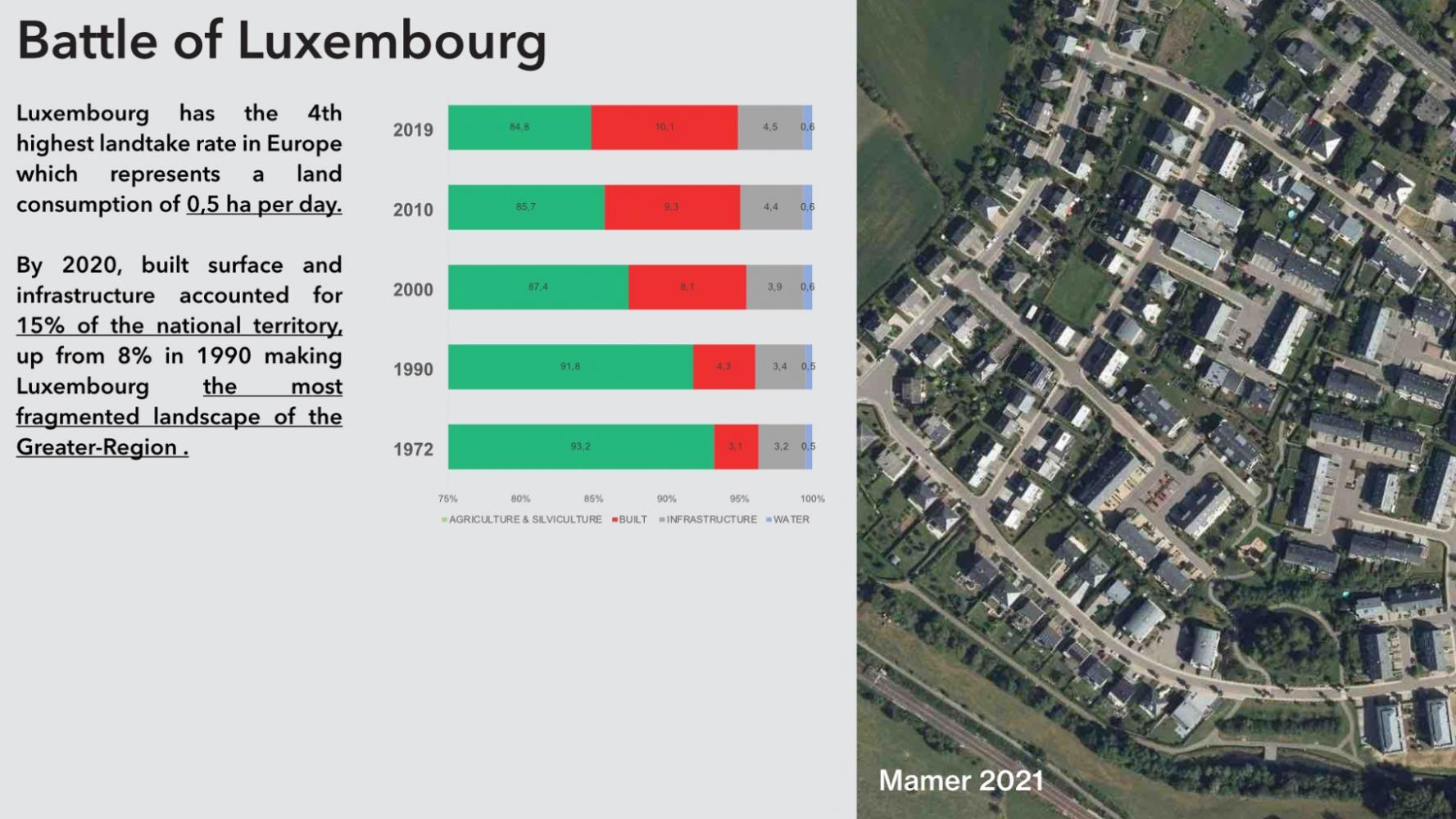

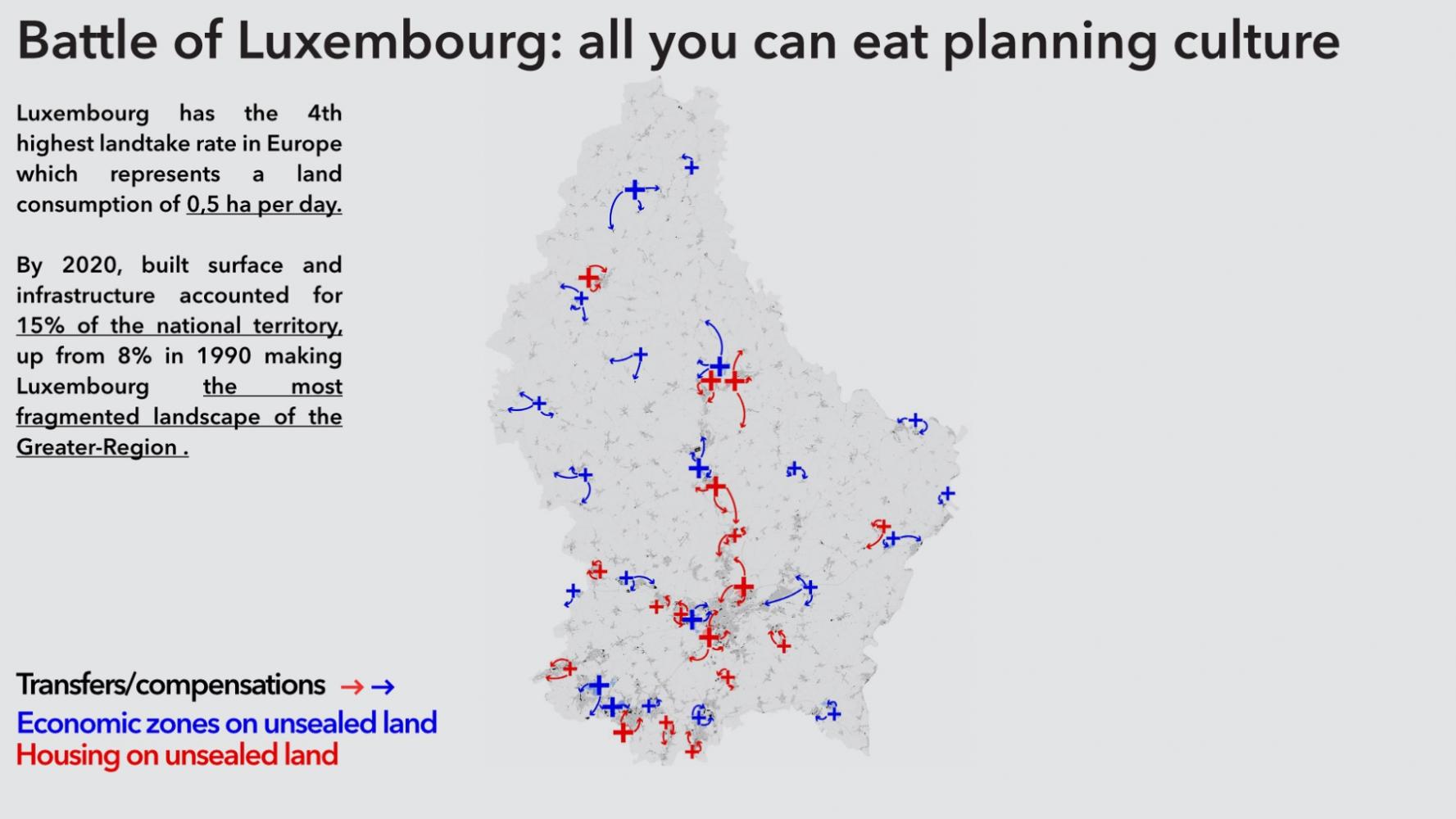

Luxembourg has the 4th highest landtake rate in Europe (EEA,2019) which represents currently a land consumption of 0,46 ha per day (Fourmann and Tholl, 2019). If the built footprint grew from 1,63% to 1,74%, roads and parking spaces flourished at the same time from 5,73% to 6,24% of the territory (Liser, 2013), making Luxembourg the most fragmented landscape of the Greater-Region .

By 2020, built surface and infrastructure accounted for 15% of the national territory, up from 8% in 1990 (Fourmann and Tholl, 2019).

Collateral damage

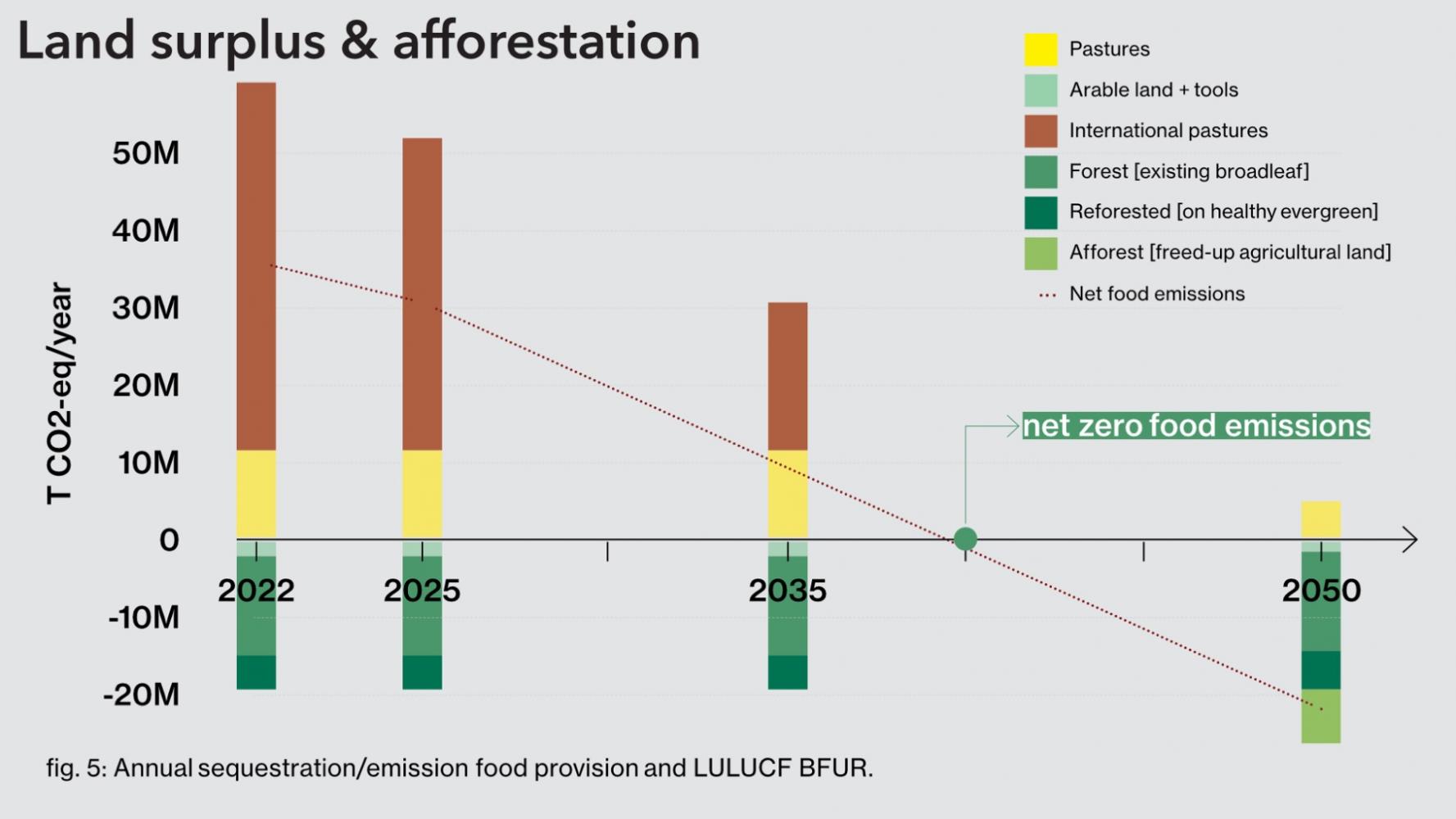

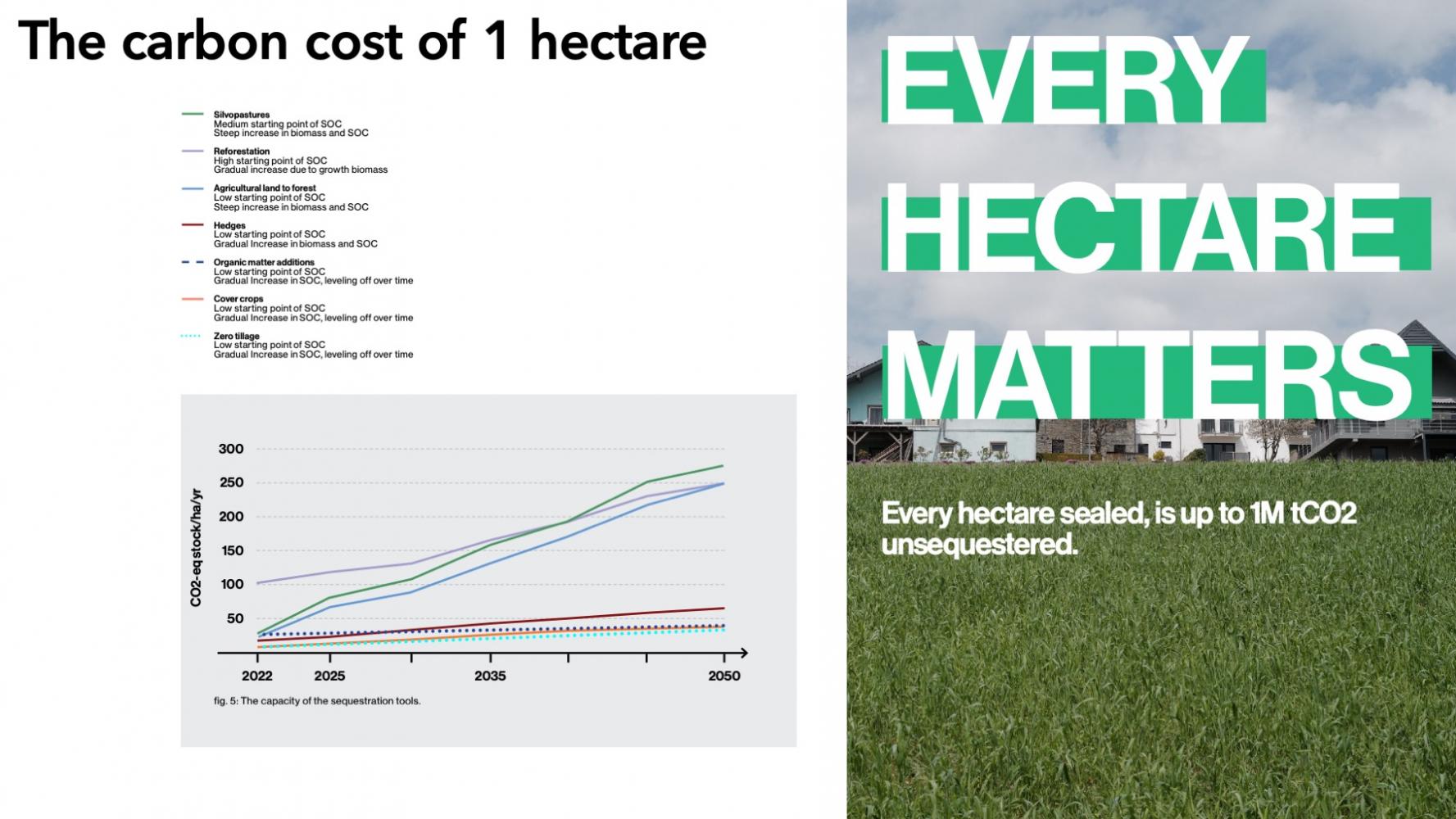

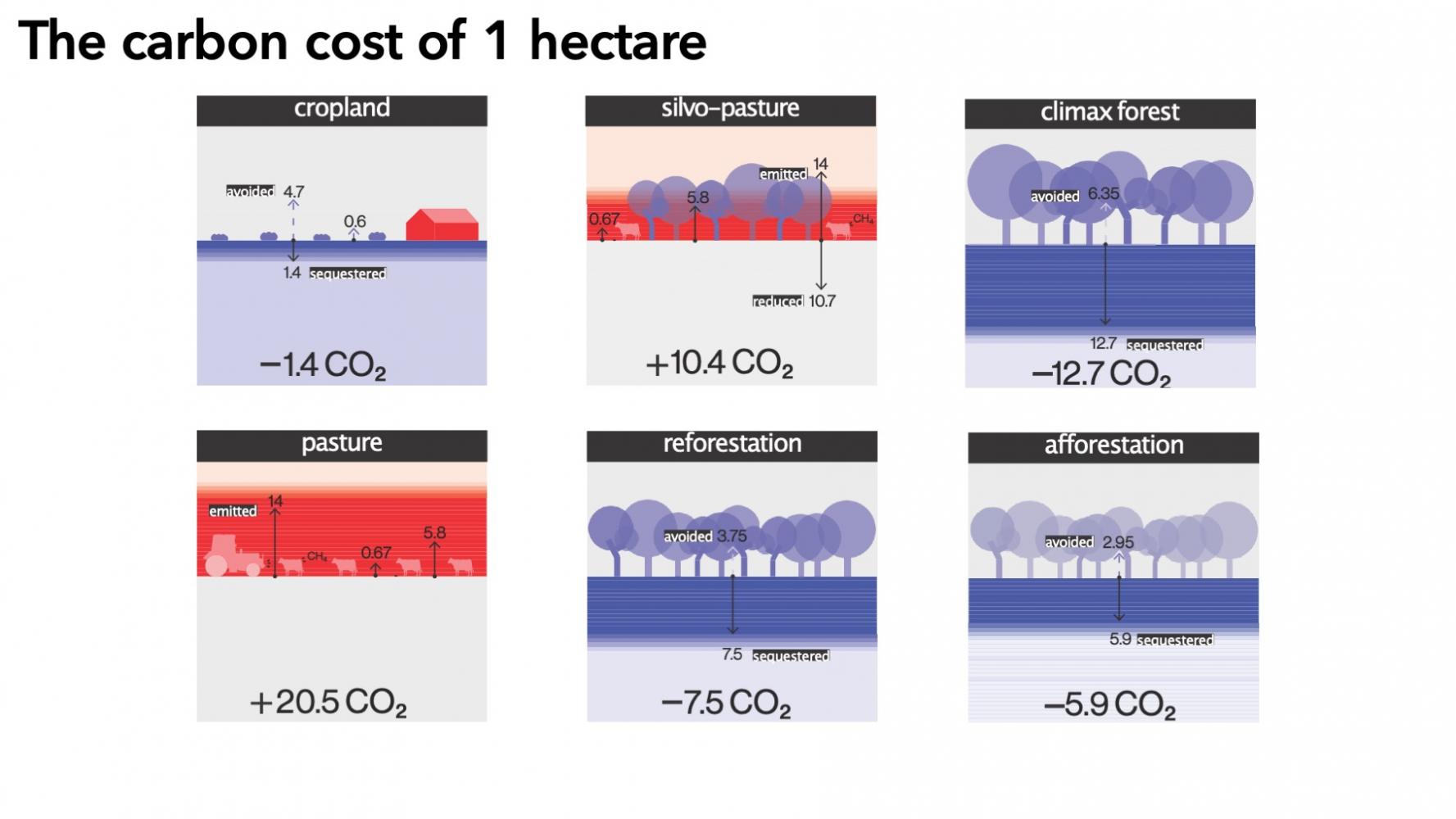

Apart from losing the capacity of sequestering up to 7,5tCO2/year (Brown et al., 1996), landtake comes at a high collateral price both for private households as much as for the public realm: the spreading of built tissue imposes the construction and maintenance of infrastructure, from roads to sewer systems. A built heritage which is becoming a structural burden for generations ahead.

Towards new vernaculars

The dissemination of the single-family home, of the activity zone hangar, of the business park building (…), collaterally provoke the weakening of social coherences and communities within villages and/or neighbourhoods and ultimately lead to the loss of (r)urban and landscape identities.

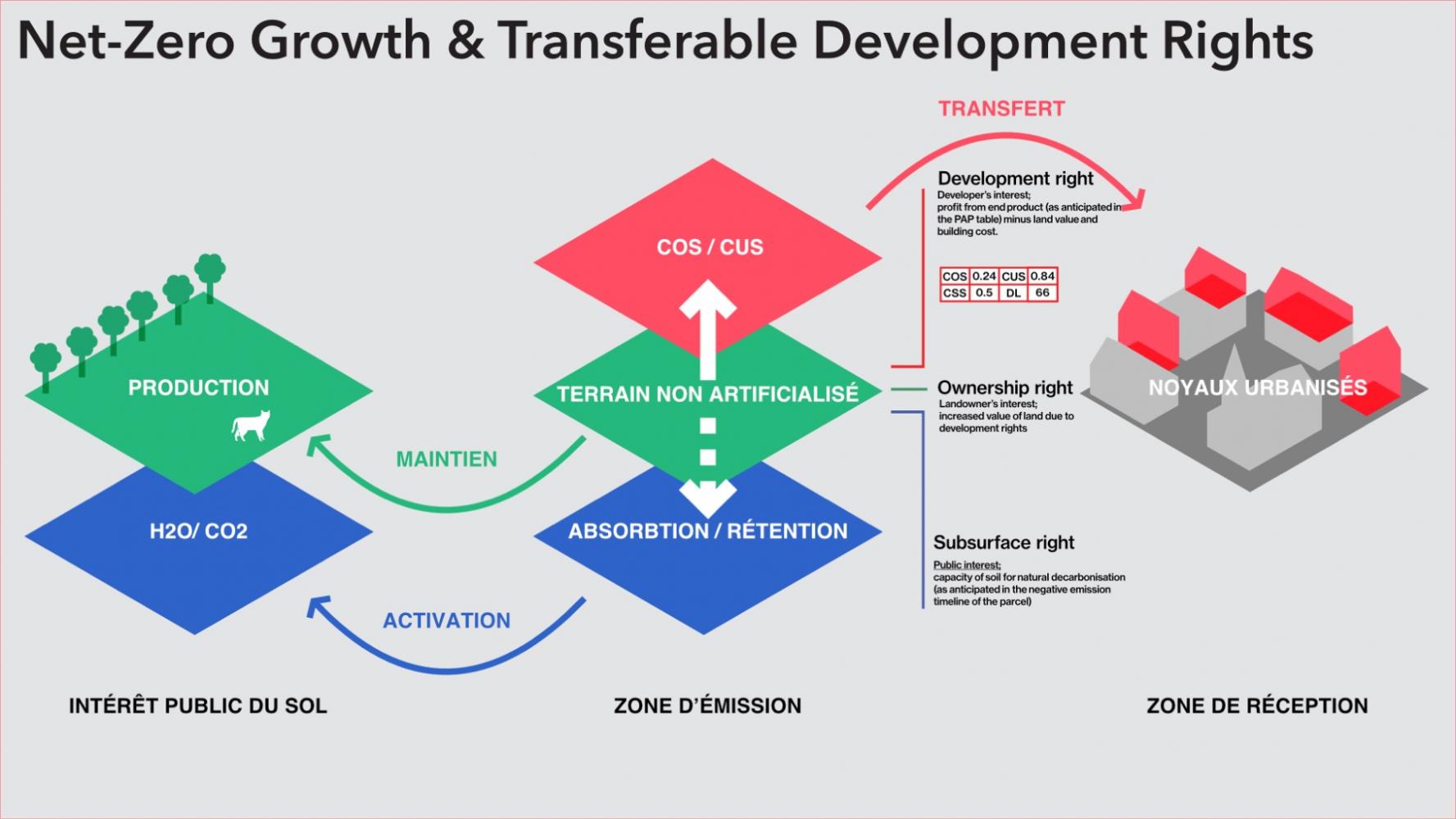

Preserving unsealed land in order to exploit its full sequestration and/or production potential can help to overcome the current status-quo of mediocre planning and building reflexes which are in fine dissolving urban structures at the cost of communities.

The objective of zero net landtake imposes the development of daring yet appropriate planning approaches resulting in locally specific built applications.

To solve the equation, underused capacities of already sealed land need to be identified, mobilized and activated, in a transitory time by tools like for instance Transferable Development Rights.

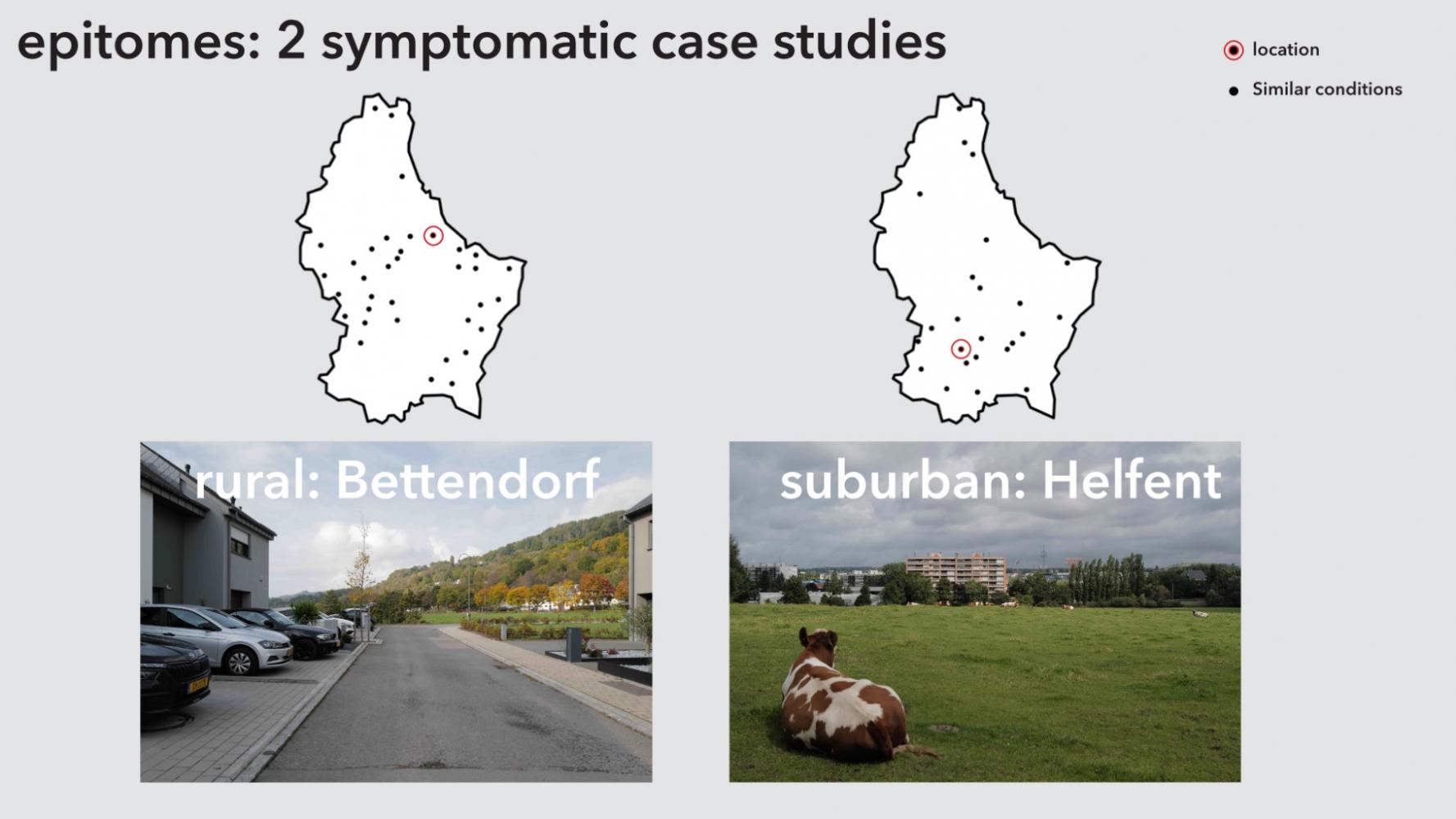

2 case studies serve as epitomes symptomatic for the region beyond its small-city urban conditions: Subarbia, & Ruralia